Assessing Luke Hughes' outlook in the transition game

4800 words breaking down Hughes' transition game and establishing a rough development plan

NOTE: If you’re an email subscriber, you might be best off opening this piece in your browser. It has lots of media and is probably best enjoyed in several segments.

The public-sphere draft consensus, brought to us by the ever-terrific Colin Cudmore, rates four (!!) 2021-eligible defencemen-- Owen Power, Brandt Clarke, Carson Lambos, and Luke Hughes, as strong candidates for top five picks.

Input from Bob McKenzie’s industry aggregate tells us that Carson Lambos, ranked 17th, should probably be excluded from that conversation from the time being (the rest of the group all cracked Mackenzie’s top ten).

Note: If we’re referencing McKenzie’s ranks, I should probably mention that some would contend for Simon Edvinsson, ranked 2nd, as deserving of a place in that top group. Personally, my most recent top three was made up exclusively of defencemen-- Hughes, Clarke, and Power, in that order (Mr. Lambos was 6th). I’ve already broken down the games of Clarke and Power; here’s Luke Hughes. The focus here is going to entirely be on his transition game-- he’s incredibly talented in that area, and to be quite honest, I got a little carried away diving in and didn’t want this piece to be unreadably long.

Thank you to InStatHockey for sourcing all the video used in this breakdown.

Born on September 9, Luke Hughes is less than two months older than the USNTDP’s Jack Hughes (unrelated, not *that* Jack Hughes), who isn’t draft-eligible under 2022. He’s the youngest of 2021’s top prospects and nearly a full year younger than Owen Power, who is already in college. Like Jack and Quinn, he’s in the development program and sits 5th in points per game through 28 games-- tops of all the team’s defencemen. With 28 points, his points/game rate of exactly one is second all-time for NTDP defenders, trailing only Flyers prospect Cam York, who played with Jack Hughes (yes, *that* Jack Hughes) and company on an obscenely stacked 2018-19 USA roster. Hughes brings much of the same dynamism and quickness that his brothers are known for, only in a 6’2” frame that Jack and Quinn are surely envious of.

One disparity between an NHL game and a WHL game-- particularly one involving two not-so-good teams-- that an observer might notice is the difference between the specific situations where a defenceman finds themselves with the puck in their own zone. Watch a WHL game-- particularly one between two not-so-good teams-- and you’ll probably see quite a bit of old fashioned dump-and-chase hockey. You’ll see a lot of pucks below the goal line and a lot of defencemen try to retrieve those pucks and make a play up-ice. Go back to the NHL of the early 2010s and it might look similar (I’m not old enough to say definitely whether or not it would be, to be honest). That game is going to have a lot more of those occasions than a modern NHL game. In a fast-paced, possession-centric league, we don’t see a whole lot of plays where a defenceman has to venture back behind his net to collect a dump-in while multiple forecheckers attempt to cause permanent damage to his brain. Dump-and-chase just isn’t a common gameplan anymore and most teams have chosen to forego the heavy forecheck in favour of a more calculated neutral zone formation. Instead, defencemen face a lot of ‘regroup’ situations-- the opponent probably just unsuccessfully attempted to enter the zone with control; the puck squirts free into the upper portion of the defensive zone; and your job as a blueliner to to grab that puck, get turned up-ice, and get the play moving forwards. Same idea, but the forecheck is usually a lot less intense-- you still have a guy pressuring you, but he’s typically more focused on taking away your passing lanes than taking your head off. It’s also generally less scripted-- on a traditional breakout, a defender usually knows that they have a winger somewhere on the boards and usually a centre swinging as an option in the middle lane. On a regroup, the three forwards could be in a variety of positions depending on the state of the backcheck when the initial turnover happened.

Hughes excels in these situations against NTDP competition. The defender is an incredibly efficient and effortless skater, able to wheel away from pressure and create an extraordinary amount of separation from forecheckers. A defenceman will typically only face one forechecker in these spots, a much easier assignment than the two that they might encounter in the deep corners. How many players do you think can contain one of the Hughes brethren one-on-one? The additional room to maneuver is also especially beneficial for a player that skates as well as Hughes; he’s able to take advantage of the room to move towards his own net and gather speed which he can then transfer up ice.

Hughes presents a difficult conundrum for forecheckers: press hard on his back and he’ll leave you lagging way behind in his tracks, but give him too much space and he can cut back across the body to go the other way.

It can be a little inconsistent, but Hughes shows plenty of upside as a passer in the transition game too. Effectively nurtured, the flashes he’s shown could develop into an important complement to his mobility in a high-level pro transition game. You don’t see any NHL defencemen consistently go end-to-end because it’s really fucking hard to do. Quinn Hughes can’t do it, Cale Makar can’t do it, nobody can. When you get to the top level of hockey, skating alone isn’t enough to be a consistently positive contributor. Mobility creates advantages-- space and time to make plays. Passing is how NHLers translate advantages into actual results-- mobility creates space, passing creates controlled exits, controlled exits create controlled entries, controlled entries create goals. At lower levels, the chain might be shorter at times (most notably end-to-end goals): skating creates controlled exits, controlled exits create controlled entries, controlled entries create goals. But better competition means greater complexity, and complex problems require several tools to solve.

The stretch pass is one of the most exciting plays a defender is capable of making: looking through several layers of defensive traffic, finding a seam, and delivering a perfect pass to spark a rush chance on the other end; it’s parallel to a successful deep shot in a game of football. Watch Hughes flip the pass into space for a forward moving across the ice here-- that playmaking upside should be clear.

And some more long passes:

The key for Hughes’ development in transition will be forming a consistent connection between his mobility and passing. Stretch passes are rare at any level of hockey. It’s the medium-level passes-- the plays where a defender draws forechecking pressure to him and then distributes to space-- that unlock opportunities for teams as they move the puck up ice. Plays like these two: grabbing pucks, curling to space, and making a quick pass up-ice to a forward gaining speed in the neutral zone.

When we look for “upside”, Hughes’ combination of mobility and distribution ability should be exactly what we key on when looking at defensive prospects. That’s how you make plays as a defenceman; those are the key traits behind just about every high-level NHL defenceman. He’s not as impactful as he used to be, but Erik Karlsson’s smoothness and game-breaking stretch pass ability made him one of the best blueliners in NHL history. That mobility/passing combo is the same thing that has made Quinn Hughes as instantly valuable as he proved last season.

Luke’s passing can be a little inconsistent when he looks to make plays at speed or under pressure. That would be one of my primary developmental focuses for him; the ability to make plays in uncomfortable situations-- when you’re moving quickly or under pressure-- is a fulcrum for effective defenders. I’m not sure if we’ve seen Hughes display the consistency or get challenged enough at the NTDP level to be fully confident in his ability to do so as he moves forward.

Hughes is clearly looking to pass here; it’s a powerplay breakout and he looks to only be going 60-75% speed moving out. But look at the reads that he misses after swerving around the first forechecker: Luke has room to wheel and options in the middle of the ice if he chooses to pass (F1’s stick has disruptive potential in that spot, but Hughes had a window to hit his forward in the centre lane or his winger on the near wall). Instead, he plays the puck up the far wall to a pressured forward. A concern of mine with Hughes is that he’s just so used to achieving near-effortless separation from pressure that he’s never really needed to rely on quick or particularly clever reads as a passer.

He doesn’t appear particularly natural making creative or high-level plays in traffic. There are just a lot of plays that don’t quite connect.

Those three plays would’ve been excellent examples of high-level utilization of space-- attracting pressure and then distributing to space elsewhere-- but Hughes just isn’t good enough at staying unbothered under pressure to execute.

Hughes is incredibly young for the draft (early September birthdate) and so he should, in theory, have a greater developmental trackway than the majority of his peers. The baseline tools are already there for a positive transitional force-- he’s incredibly mobile and he has a strong eye for long passing options on the breakout. He needs to learn to connect those skills by achieving greater consistency in his reads and execution as a passer.

How can he do that? The easy answer is “more reps”, but let’s try to go a little further than that. Hughes’ vision as a passer is impressive, but I wouldn’t categorize him as being particularly quick to go through his progressions and key in on a read. So the question-- or at least a starting position-- becomes “how can Hughes increase his processing speed?”. Again, the easy answer seems to be more reps, but we want more than that. This terrific piece by Evan Zaucha about the science and detail behind “feel” in basketball should be a must-read for anybody looking to further their understanding of intelligence in sports: Zaucha, who has a background in neuroscience, concludes that there is no distinct or proven way to improve a player’s feel, but developing drills with high levels of complexity or even changing rules is a strong way to engage and improve a player’s brain processes. The goal should be to simulate game situations where a player has to make a split-second decision. Small-area games are a good tool; reducing the time and space of a player forces them to make faster decisions or run into trouble. These are already a common practice tool, but where they become a little less effective, I think, is when the space lost by limiting the player surface is offset by reducing the number of players in that space to only four (two vs two, the most common setup I remember from my minor hockey practices). As a general rule, I’d want at least three players per team in any given small-area drill. Not only does it limit the available space even more, but presenting two passing options increases the load on a player’s brain when they possess the puck. Your options are pretty straightforward when you only have one teammate-- you either pass or keep. Add a second teammate and you have to weigh your passing options before making a play; that’s an environment where a player can improve his ability to evaluate his reads and make the best possible play.

Let’s move on: How does Hughes get involved in the offence? His statistics speak for themselves. At over a point per game, he’s clearly doing it rather frequently. Everything as a defenceman starts on the breakout, but putting up offensive numbers at five-on-five means extending controlled exits into controlled entries. Cale Makar led the entire NHL in 5v5 points per sixty minutes as a rookie last season.

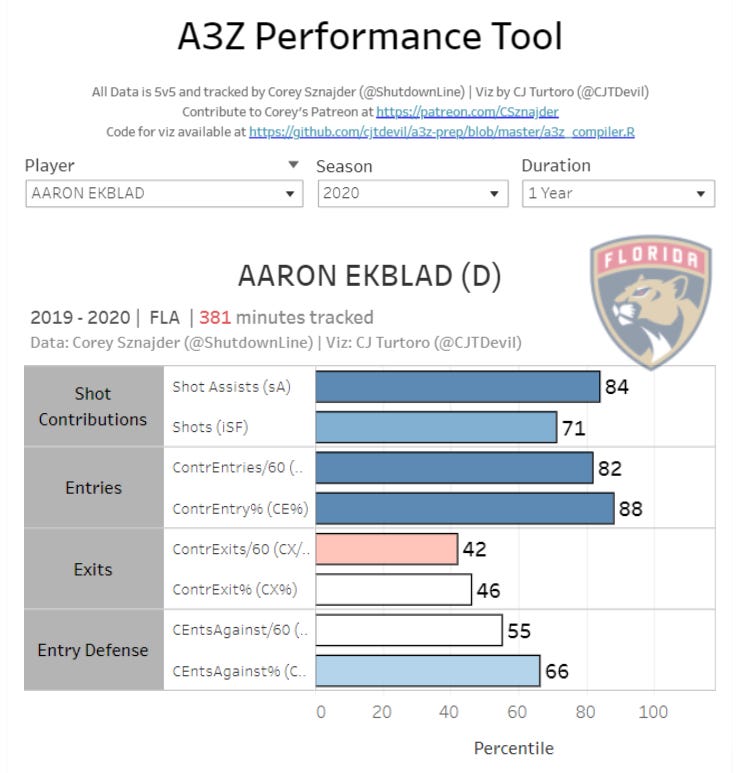

Look at that beautiful dark blue in both the exit and entry categories. Compare that to Ethan Bear, another rookie, who posted strong offensive shot attempt figures (Bear was 20th in the NHL in shot attempts for per sixty minutes relative to his team) but was only 82nd in 5v5 points per sixty.

Distinctly above-average at exiting his zone, but below par at entering the opponent’s end of the ice. That means fewer offensive possessions and fewer opportunities to get on the scoresheet. The ideal defenceman, like Makar, can do both. The good defenceman, like Bear, can do one. Aaron Ekblad, a good defenceman, has below-average exit numbers but very strong entry numbers.

Ekblad is an elite point producer-- sixth among NHL defencemen in 5v5 points/60 last season-- with top-level on-ice offensive results too (31st in 5v5 shot attempts for per sixty minutes). We can see how his entry abilities translate into shot contributions at a higher level than Ethan Bear-- compare the top two bars on their respective charts. They both have strong on-ice numbers, but they come from different sources: Ekblad jumps into the play frequently and is individually responsible for a higher percentage of his on-ice shot attempts, whereas Bear puts his teammates in strong positions to go down-ice and get shot attempts without being individually involved in those shot attempts himself. Both the Panthers and Oilers are extremely happy to have their respective defencemen in their lineups.

Can Luke Hughes activate into the offence and make plays at the offensive blueline, like a Cale Makar or Aaron Ekblad, or will his contributions largely diminish once the puck exits his own zone (like Ethan Bear)? This is a really difficult area to project in any young defenceman, but again, let’s try to go a little deeper. What are some indicators demonstrated by defencemen with particular skill at entering the offensive zone with control?

I mean, we just have to look at Cale Makar here, don’t we? Don’t think we can just ignore that 97th percentile result for his rate of controlled entries. Here’s a look at what he can do:

A few things here stand out to me:

Smooth backwards-forwards pivots, highly explosive out of those positions.

Very good at identifying lanes to activate off the puck.

Incredibly confident and deliberate when he chooses to activate. Appears almost tunnel-visioned with how determined he is at bringing the puck through the neutral zone himself, but he’s fully capable of doing things himself.

Navigates pressure extremely well-- a combination of his puck skills and confidence. Can move through dense ice and come out the other side with possession.

Makar has undergone quite the growth trajectory, moving from well over a point per game in the AJHL in his draft year, to over a point per game in his final NCAA season, and now operating at about a point per game early in this NHL season. He doesn’t seem to have added any new skills in the zone entry department though, just developed them further.

ese sequences are from Makar’s lone WJC appearance back in his DY+1 season in 2017-18. That’s as far back in time as I can go. Watching that video, the similarities are clear. The difference in competition is vastly different, but the same skills power Makar’s entry success: the ability to navigate pressure, smooth skating, identification of opportunities to get involved without the puck. All of Makar’s entry framework was already present before he broke into the NHL.

Let’s establish Hughes’ entry framework and go from there. In his current environment, his skating is the backbone behind all of his transition work. His ability to push defenders back with the threat of his speed unlocks a tremendous amount of space for him as he moves forward with the puck, allowing him to largely avoid any type of defensive encounter until he’s already gained the offensive blueline.

NHL defences are a lot more aggressive than any competition Hughes has/will ever face with the U18s. That’s why the professional European leagues can actually be a strong evaluation environment even as most of the draft eligibles play only bit roles for their clubs; the players that can handle and make things happen out of uncomfortable spots on the ice are often the ones that go the furthest in the sport. Luke Hughes is rarely uncomfortable against USHL competition, and only a little more so against the NCAA teams that the program faces. But every player has moments where they are challenged; if we can sniff out moments where Hughes has been forced to go beyond his skating, we can get a sense of what traits he’ll eventually lean on to complement his mobility in the NHL someday, when those moments are commonplace.

This one starts with Hughes skating through the neutral zone on what becomes a 2v2. The Lincoln defenceman stunts towards him a pokecheck; Hughes doesn’t have quick enough hands to counter the challenge and remain on course down ice. The rush dies.

He tries to dangle this defender, but does nothing to set up the move. Even if he does somehow pull off this move, Hughes would have been hard pressed to get a shot off before the other defenceman or the goaltender’s stick disrupted him.

Man, this play started with a nice activation up the left wall and then just went to hell from there.

Attempts to beat the defender wide this time, but he’s not deceptive or crafty enough to make anything of it. He needs to add a speed change, some kind of fake, anything to force a split-second of hesitation for this defender.

Realistically, and this wasn’t really much of an option for him on that last play, Hughes will be looking to stop up and make a play far more often than he’ll try to beat a defender wide. The good news is that Hughes displays greater control in those situations than when he tries to do things himself. As a defenceman, Hughes is a lot more used to having an opposing player bearing down on him than being the one attacking a defender. Forcing the defender to challenge him puts him in a more familiar setting.

This sequence is a nice demonstration of the point. He dices through a pair of forwards in the neutral zone like it’s nothing, but he can’t turn it into anything when he attacks the last defender.

This forward tries to stand him up near the line, Hughes steps around him and makes an entry pass. Beautiful stuff.

This clip is exceptional. Finds a lane to activate, the defender steps up on him, Hughes manages to spin off and maintain possession moving down the wall. That’s a dangerous play-- spin a half-second late and you go head first into the glass-- but Hughes executes it perfectly. That’s making something out of an uncomfortable situation.

There are occasions where Hughes runs into a little bit of trouble when facing a defensive challenger, but he doesn’t look anywhere near as uncomfortable as he does trying to act as the challenger. This defender forces the uncontrolled entry by stepping on Hughes.

So, what is Hughes’ entry framework? He’s incredibly mobile, we’ve established that several times over. He’s confident too, persisting in attacking defenders even through inconsistent results. And he flashes plenty of comfort in situations where defenders step up on him, a green arrow as to his ability to make plays entering the offensive zone. He does well picking his spots to activate without the puck to become a feature of the rush and improve his team’s numbers. Those are the skills that he’ll look to build upon in his development.

So, with what we’ve found so far, let’s try to etch out a development plan for Hughes’ game in transition. To reach his best-case development arch, Hughes should strive to improve his puck skills as he takes on defenders off the rush and become more decisive and explosive in his activations.

Hughes is committed to the University of Michigan beginning next season. A trio of 2021 draft eligibles are already with the program: Matty Beniers, Kent Johnson, and most relevant, defenceman Owen Power. Crafting a strong environment for in-game development is a balancing act: you want a player to feel challenged and uncomfortable while still remaining competent enough at the level to maintain a regular and important role with their team. Skill players not ready for the level they are at often fall into bottom-six or bottom-pair roles where they are expected to provide value in ways other (defence, toughness) than their actual strengths (offence, puck skills). Players that linger too long at a level where they dominate, like Alexis Lafreniere in the QMJHL last year, aren’t under frequent enough duress to be forced to expand their game beyond their old tricks. In his current spot with the U18s, I feel that Hughes is nearing that position where he isn’t particularly challenged, especially going against a forecheck-- he can absolutely dice up USHL forecheckers. I still think it’s a good environment for his development though-- the NCAA competition puts a little pressure on him going back to collect pucks and the NTDP is a strong out-of-game growth environment.

What should we expect from Hughes with Michigan? There are two opportunities for us to gain some insight. The U18s haven’t played many D1 opponents this year because the big NCAA conferences are playing only within conference due to COVID-19, but they played two games against ASU very recently and one versus Bowling Green earlier in the season. As I write this, I’ve yet to watch those three games. Ideally, we’ll see Hughes look uncomfortable against what should be a stronger forecheck, forcing him to lean on some of his secondary tools in response. We can also look to fellow 2021 eligible Owen Power, a freshman at Michigan, to see the environment for a first-year defenceman in this particular NCAA program.

Unfortunately, ASU and Bowling Green aren’t the very best of NCAA programs. COVID robbed us of the opportunity to watch Luke Hughes and the rest of the U18s go up against the trio of 2021 eligibles already at the University of Michigan, and we also would’ve got to see Hughes go up against the premier talent at programs like Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Boston University. Hughes’ counter of opposing forechecks still looked effortless at times, but there were some weak moments for him too.

An area for development for Hughes should be his entry passing. His stretch passes are promising, but his short passes near the line lack the quickness and deception required to set up forwards in space crossing the line.

Here’s a good example versus ASU: he goes against the grain of Arizona’s neutral-zone forecheck and sends his forward in with tons of space down the near wall (I have no idea what’s going on with ASU’s positioning here, but Hughes takes advantage).

And now a not-as-good example-- the only thing this pass does is put his forward in a worse spot than Hughes was in when he looked to make the pass.

Hughes will need to rely on that passing when he doesn’t have room to skate. He doesn’t look particularly comfortable making those plays yet.

More promising was the deceptiveness that Hughes mixed in to create space and really enable his mobility to shine through against more effective forecheckers. That’s a translatable skill that he can use to maximize the value of his skating.

This is a real subtle fake that creates tons of time and allows Hughes to jumpstart the transition game with a stretch pass.

This stop-up shakes the forechecker, creating plenty of time again.

And this little head fake towards the far boards gets the forechecker on his outer hip and lets Hughes wheel out of there.

The opposition is forcing him to involve tools beyond his skating. Hughes brings in his deceptiveness and beats the forecheckers.

Next year, Hughes will enter the University of Michigan in circumstances that are really quite similar to what Owen Power faced at the beginning of this season (minus, hopefully, the whole pandemic element). He’s coming out of very good USHL team (the NTDP also plays against NCAA comp, of course), The NTDP plays plenty of USHL competition, they’re a very strong team in that league, and Hughes will be looking to expand beyond his skating in his transition toolbox. Power played for the USHL superpower Chicago Steel and was very reliant on a combination of his 6’5” frame and impressive mobility to make him the best defenceman in the United States league last season. At Michigan, Power has still been successful in skating the puck, but he’s shifted more towards using his large frame to ward off forecheckers and connect with his forwards in space via the pass.

That’s what should make the NCAA a really excellent environment for the next stage of Hughes’ development. The level of forechecking should exceed what he would face in the CHL or USHL, forcing him to rely further on a somewhat underdeveloped part of his game-- his short-to-mid ranged passing. College programs play about half as many games as a CHL team would too, making it an ideal place for players that might be a little bit on the rawer side to develop their skills outside of gameplay. I theorize that one of the driving reasons behind the ascent of the USHL-NCAA pathway is the stark contrast in level of play between the two: elite players can really hone their signature skills in junior against so-so competition before being thrust into an environment where they are expected to play an all-around game and have lots of practice time to hone that style. The gameplay forces them to lean on their secondary and tertiary skills more than ever before, but balancing that demand with increased practice makes it a realistic challenge.

I think Hughes’ eventual readiness to jump from the NCAA to a higher level should be primarily judged by his comfort level on the breakout; probably most effectively measured a combination of zone exit metrics and visual assessment. I’m not familiar enough with microstatistics to offer up a target number (ideally I’ll one day have access to all the tracking patreons out there to become better versed in that area), but I’d be looking for Hughes to hit a certain percentage of controlled exits compared to total exit attempts as an indicator that he’s ready to move on. As for visual clues: you want every breakout to appear like a challenging problem that requires Hughes to consider multiple of his own tools to solve. His skating shouldn’t be the dominant feature of his transition portfolio, we want to see a mix of mobility, deception, and passing. Effortlessness is a bad thing when we’re talking about developmental environments.

Okay, so we’re fastforwarding a year or two into the future. Hughes is too good for college, he’s signed his ELC, and he’s at training camp. NHL or AHL? Hughes will be a high draft pick with a presumably strong NCAA record. Unless his training camp is poor or his team has incredible defensive depth, he should be a no-brainer for his nine games (more than that means his contract doesn’t slide, which can be good or bad depending on the circumstances but is usually perceived as a bad thing). I think it usually tends to be pretty clear when a rookie is immediately deserving of an NHL spot. For defencemen, I like the idea of easing them into the league in a consistent third-pairing role-- they should be playing every single game, but the third-pair means a team can experiment with their level of competition and allow the player to play through their mistakes. It’s just like the transition into the NCAA: some mistakes and an apparent lack of comfort should be expected, and can often be a good thing. High-level players usually just need a bit of time to figure out exactly what works for them at a new level.

So, to recap the poorly organized words that you just read, I present to you the Luke Hughes Development Plan, summarized:

Join the University of Michigan next season as planned. Focus on short-to-medium length outlet passing, growing as a deceptive puckhandler on the breakout, and expanding his transition toolkit to encompass more than just mobility and stretch passing.

Once he hits a level where a set majority of his zone exit attempts end in controlled outcomes and he appears visibly comfortable against NCAA forechecks most of the time, sign the ELC and turn pro.

Play nine NHL games in his rookie season. If he isn’t a clear drag on the team and there is room for him to play an everyday role on the third pair, keep him with the NHL club. If he isn’t better than six defencemen already on the roster (unlikely) or the coach doesn’t want to play him, send him to the AHL. Repeat step 2 at that level, then promote him. Remember, discomfort is good! Mistakes are good! Those are what spark development.